15. To maintain a rotor at a uniform angular speed of 200 rad s–1 , an engine needs to transmit a torque of 180 Nm. What is the power required by the engine?

(Note: uniform angular velocity in the absence of friction implies zero torque. In practice, applied torque is needed to counter frictional torque). Assume that the engine is 100 % efficient.

Solution:

Angular speed of the rotor, ω = 200 rad/s

Torque required, τ = 180 Nm

The power of the rotor (P) is related to torque and angular speed by the relation:

P = τω

= 180 × 200 = 36 × 103

= 36 kW

Hence, the power required by the engine is 36 kW.

16. From a uniform disk of radius R, a circular hole of radius R/2 is cut out. The centre of the hole is at R/2 from the centre of the original disc. Locate the centre of gravity of the resulting flat body.

Solution:

R/6; from the original centre of the body and opposite to the centre of the cut portion.

Mass per unit area of the original disc = σ

Radius of the original disc = R

Mass of the original disc, M = πR2σ

The disc with the cut portion is shown in the following figure:

Radius of the smaller disc = \(\frac R2\)

Mass of the smaller disc, M’ = \(\pi (\frac R2)^2 σ = \frac 14 \pi R^2 σ = \frac M4\)

Let O and O′ be the respective centres of the original disc and the disc cut off from the original. As per the definition of the centre of mass, the centre of mass of the original disc is supposed to be concentrated at O, while that of the smaller disc is supposed to be concentrated at O′.

It is given that:

OO' = \(\frac R2\)

After the smaller disc has been cut from the original, the remaining portion is considered to be a system of two masses. The two masses are:

M (concentrated at O), and

-M'(= \(\frac M4\) ) concentrated at O′

(The negative sign indicates that this portion has been removed from the original disc.)

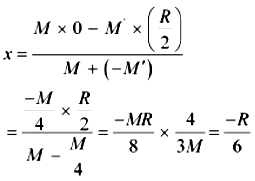

Let x be the distance through which the centre of mass of the remaining portion shifts from point O.

The relation between the centres of masses of two masses is given as:

x = \(\frac {m_1r_1 + m_2 r_2}{m_1 + m_2}\)

For the given system, we can write:

(The negative sign indicates that the centre of mass gets shifted toward the left of point O.)

17. A metre stick is balanced on a knife edge at its centre. When two coins, each of mass 5 g are put one on top of the other at the 12.0 cm mark, the stick is found to be balanced at 45.0 cm. What is the mass of the metre stick?

Solution:

Let W and W′ be the respective weights of the metre stick and the coin.

The mass of the metre stick is concentrated at its mid-point, i.e., at the 50 cm mark.

Mass of the meter stick = m’

Mass of each coin, m = 5 g

When the coins are placed 12 cm away from the end P, the centre of mass gets shifted by 5 cm from point R toward the end P. The centre of mass is located at a distance of 45 cm from point P.

The net torque will be conserved for rotational equilibrium about point R.

10 x g (45 - 12) -m'g (50 -45) = 0

∴ m'= \(\frac {10\times33}{5}\) = 66 g

Hence, the mass of the metre stick is 66 g.

18. A solid sphere rolls down two different inclined planes of the same heights but different angles of inclination.

(a) Will it reach the bottom with the same speed in each case?

(b) Will it take longer to roll down one plane than the other?

(c) If so, which one and why?

Solution:

(a) Yes (b) Yes (c) On the smaller inclination

(a)Mass of the sphere = m

Height of the plane = h

Velocity of the sphere at the bottom of the plane = v

At the top of the plane, the total energy of the sphere = Potential energy = mgh

At the bottom of the plane, the sphere has both translational and rotational kinetic energies.

Hence, total energy = \(\frac 12 mv^2 + \frac 12 l\)ω2

Using the law of conservation of energy, we can write:

\(\frac 12 mv^2 + \frac 12 l\) ω2= mgh ....(i)

For a solid sphere, the moment of inertia about its centre, I = \(\frac 25 mr^2 \)

Hence, equation (i) becomes:

\(\frac 12 mv^2 + \frac 12 \) (\(\frac 25 mr^2 \))ω2 = mgh

\(\frac 12 v^2 + \frac 15 v^2\) = gh

v2 (\(\frac {7}{10}\)) = gh

v = \(\sqrt{\frac {7}{10}}gh\)

Hence, the velocity of the sphere at the bottom depends only on height (h) and acceleration due to gravity (g). Both these values are constants. Therefore, the velocity at the bottom remains the same from whichever inclined plane the sphere is rolled.

(b), (c) Consider two inclined planes with inclinations θ1 and θ2, related as: θ1 < θ2

The acceleration produced in the sphere when it rolls down the plane inclined at θ1 is: g sin θ1

The various forces acting on the sphere are shown in the following figure.

R1 is the normal reaction to the sphere.

Similarly, the acceleration produced in the sphere when it rolls down the plane inclined at θ2 is: g sin θ2

The various forces acting on the sphere are shown in the following figure.

R2 is the normal reaction to the sphere.

θ2 > θ1; sin θ2 > sin θ1 ... (i)

∴ a2 > a1 … (ii)

Initial velocity, u = 0

Final velocity, v = Constant

Using the first equation of motion, we can obtain the time of roll as:

v = u + at

∴ t ∝ \(\frac 1a\)

For inclination θ1 : t1 ∝ \(\frac 1{a_1}\)

For inclination θ2 : t2 ∝ \(\frac 1{a_2}\)

From equations (ii) and (iii), we get:

t2 < t1

Hence, the sphere will take a longer time to reach the bottom of the inclined plane having the smaller inclination.