New research highlights the potential of implantable sensors in enhancing bone healing through data-enabled resistance training.

Scientists at the University of Oregon have developed tiny implantable sensors that monitor bone recovery in real-time. In a recent study, rats with femur injuries underwent an eight-week resistance-training program, showing substantial improvement in healing.

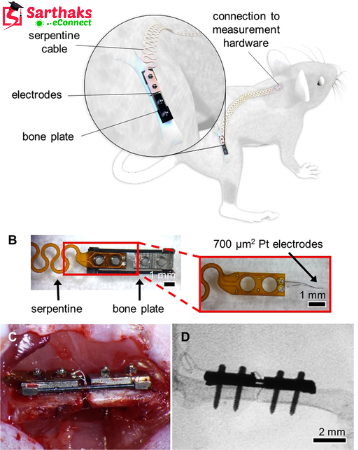

These innovative sensors, designed at the UO’s Phil and Penny Knight Campus for Accelerating Scientific Impact, are implanted directly at injury sites, where they provide detailed, continuous data on the bone’s mechanical properties as it heals. If adapted for human use, this technology could offer a way for healthcare providers to create personalized rehabilitation plans, adjusting exercise regimens based on real-time recovery data.

Collaborative Research and Promising Findings

This study is the result of a collaborative effort between the research teams of Bob Guldberg, Nick Willett, and Keat Ghee Ong at the Knight Campus. It is funded in part by the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance, with their findings published on December 12.

Bob Guldberg, Director of the Knight Campus and the study's senior author, emphasized that the data from their research supports early resistance rehabilitation as an effective method for boosting bone formation, strengthening bone healing, and restoring the mechanical properties of the bone to pre-injury levels.

The Goldilocks Principle in Recovery Exercise

The research supports the well-known "Goldilocks" principle of post-injury exercise: recovery is hindered by either too little or too much activity, but the right amount can accelerate healing. Determining the ideal exercise type and intensity for optimal recovery can be complex, as it differs between patients.

The specialized sensors created at the Knight Campus offer a new approach by providing real-time insights into the healing process. Initially developed through collaboration between the labs of Ong and Guldberg, these sensors were further enhanced by recent doctoral graduate Kylie Williams.

Testing Resistance Training for Bone Healing

In this study, the researchers sought to test the effects of resistance running, a form of recovery exercise, on bone healing. To do so, they designed custom brakes for rodent exercise wheels, creating resistance similar to an inclined treadmill.

Rats with femur injuries, equipped with the implantable sensors, ran on either regular or resistance-modified exercise wheels. Throughout the eight-week study, the sensors transmitted strain data, offering valuable insights into the mechanical forces acting on bone cells during the recovery process.

At the conclusion of the study, the resistance-trained rats showed noticeable signs of bone healing, with their tissue density greater than that of the sedentary or non-resistance groups. The resistance-trained rats' injured bones displayed mechanical properties, such as stiffness and torque, that were comparable to uninjured bones.

These findings suggest that resistance training can significantly improve bone recovery, even in the absence of biological stimulants or drugs, as highlighted by Guldberg.

Potential Clinical Applications of Resistance Rehabilitation

Biological agents like BMP (bone morphogenetic protein), which promote bone growth, are commonly used in regenerative medicine. However, Bob Guldberg’s team has demonstrated that complete functional recovery of bone can be achieved through resistance training alone, highlighting its potential for clinical use.

According to Kylie Williams, the study's lead author, “One of the most significant aspects of our work is that we’ve shown resistance rehabilitation can restore femur strength to normal levels in just eight weeks, without the need for biological stimulants. We are extremely excited about that outcome.”

Limitations and Future Research

One limitation of this study was that all animals received the same level of resistance during the entire experiment. However, the research team is currently exploring how varying resistance levels over the course of recovery might impact bone regeneration.

Promising Results and Future Prospects

Although the research was conducted with rodents, the team is optimistic that this data-enabled rehabilitation approach can be adapted for human patients suffering from musculoskeletal injuries. In collaboration with Penderia Technologies, a Knight Campus start-up, the team is working on improving the implantable sensors, including making them battery-free and developing wearable versions for easier use in humans.

After completing her doctoral studies, Williams will join Dr. Ong and the expanding Penderia team to further investigate how these sensors can be translated into clinical applications.

Guldberg expressed his optimism, stating, “We are hopeful that this research will eventually be applied in clinical settings, where these sensors can provide personalized data tailored to the type and severity of injury, helping inform more effective rehabilitation strategies.”